This interview first appeared in the CowboyJackClement.us newsletter, January 2011 – the work of J. Niles Clement

Tell us about your childhood and how you got into music.

I grew up in a place called Dedham, Massachusetts, about 12 miles southwest of Boston. It was a pretty quiet town, and there wasn’t any music in it. The first live music I ever heard was the Boston Symphony Orchestra. We went in on a school trip to Symphony Hall in Boston. It was fantastic, and it made a big impression on me, seeing all those people on the stage playing together. Of course, I thought the job was for me was the conductor’s because he didn’t seem to have to know how to play an instrument. All he did was stand up there and wave his stick around, and he took all the bows and applause, so that appealed to me. I would stand at home in front of the mirror with a stick while playing my sister’s classical records, pretending to be the conductor! I took piano lessons. A lady, Miss Davis, came to the house once a week. It didn’t get me too far, but I did learn how to read music during that time, which was a good thing for me. I wasn’t interested in practicing, so eventually that was dropped. Music wasn’t a big factor in my life at that time.

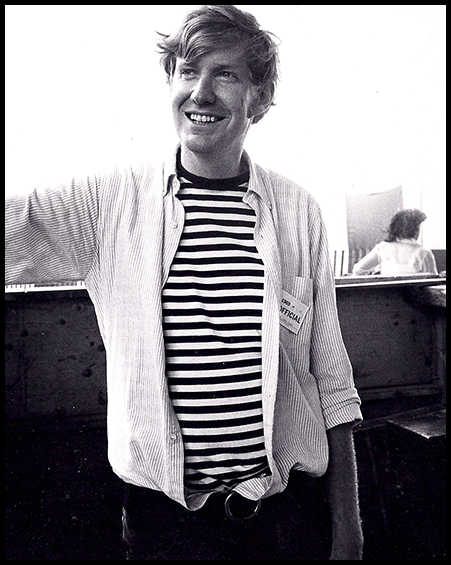

Rooney’s first beer – not his last

In 1951, when I was around 13, a friend of mine from school, Dick Curley, said, “You have to listen to this show on the radio, it’s the funniest thing you’ve ever heard.” It was the Lilly Brothers, Don Stover and Tex Logan, and they called themselves The Confederate Mountaineers. They had a live show on the radio every night from 7:45 to 8 o’clock. So I listened, and I had never heard anything like this before in my life. They were a great band. Tex Logan was a great fiddler, the Lilly Brothers were wonderful singers, and Don Stover was a great banjo player. They all had real southern accents and would say stuff like, “Howdy friends and neighbors,” using the country spiel that everybody did. I started listening to them every night. After their show at eight o’clock, this disc jockey came on. He was a real Down East kind of character. His name was Nelson Bragg, and he called himself The Merry Mayor of Milo, Maine. He was very funny and entertaining at the time. Of course, Hank Williams was at his height. Lefty Frizell was becoming a big star, and Hank Snow, and Hank Thompson. I was listening to all this stuff, and I just got hooked on it.

I especially got hooked on Hank Williams. Dick Curley told me about some shows at Symphony Hall called The Hayloft Jamboree. So we went down there and the first big star I saw was Slim Whitman, who was very big at that time. He had a lot of hits. They also had a lot of local bands on the show, like The Confederate Mountaineers, and a guy named Jerry Devine, who sounded like Hank Snow, and another guy named Al Green, who sounded like Eddy Arnold. There was a band from Providence called Eddie Zack and the Dude Ranchers. They were a Western Swing, Pee Wee King style band. I went another time and saw Mother Maybelle and The Carter Sisters, June, Helen, and Anita. I also saw Homer and Jethro. These shows would happen once a month. In 1952, we went down to the seashore for the summer. My folks had built a little cottage down there. We didn’t have a phone or anything, so I was kind of out of touch. I did listen to the radio on Saturday night. CBS had a network show called Saturday Night Country Style. They had feeds from all the major country shows, like from Wheeling, West Virginia, the Big D Jamboree from Dallas, The Louisiana Hayride, and one from Knoxville, which is where I first heard Chet Atkins . Richmond, Virginia, had the Old Dominion Barn Dance. Mac Wiseman was on that show. I heard Elvis Presley for the first time in ’54 on the Louisiana Hayride singing, “Blue Moon Of Kentucky”, and I’ll never forget that. My uncle Jim noticed me listening to the radio and strumming along on a tennis racquet. He said, “That boy needs something else,” and he bought me a little Roy Smeck ukulele. He showed me a few chords and I got a book. I subscribed to Country Song Roundup Magazine, which published the lyrics to all the hits, and, as it turned out, I had a natural ear. I could tell when I needed to change a chord. Webb Pierce had a big hit called, “Backstreet Affair” at that time. I could hear that on the radio, have the words from the magazine, and I could just play it, strumming along. I didn’t know anything and I didn’t know anyone who was playing this kind of music, so I picked the thing up backwards, because I’m left-handed. So I was playing upside down and backwards but it didn’t seem to make any difference. I was learning all the Hank Williams songs. Hank Williams died on New Year’s Day in ’53, and within a month MGM released a memorial album, all purple and everything. My brother John had bought me two Hank Williams albums of 78’s, “Moaning The Blues” and “Luke The Drifter”. Hank’s sister, Irene, started a column in Country Song Roundup about Hank. I was totally obsessed with Hank Williams! I wanted to be Hank Williams! I wrote her a letter and said, “I’d like to write a book about Hank Williams. Would you send me some information”, and of course I never heard a word from her. When I came back from the beach that fall of ’53, my schoolmate, Bob Holland, said he had a plywood guitar he would sell me for $12. I bought the guitar and it came with a little canvas sack with snaps on it. It was a brutal guitar to play, the action was so high on it. I thought I should change the strings around, due to my left-handedness. But I tried that and they seemed to buzz and rattle. I didn’t know anything really, so I didn’t change the nut. I just changed the strings, so the strings were just buzzing and rattling, but I wanted to play right away. It didn’t seem to matter, I knew I wasn’t going to be Chet Atkins. I just wanted to strum along like Hank. So I left the strings the way they were and started playing that guitar. It was brutal to learn how to play, but I did it. I suffered through it all and I got to where I could play okay. The guitar came with a finger pick that I put it on my index fingernail because I thought that’s what you should do, and I was just started strumming.

Every Saturday afternoon they had a live radio show from a studio in the radio station. We had gone in there several times to see The Lilly Brothers. We’d just go in and put our noses against the control room window and look at them. One afternoon, these two girls were on there and trying to sing like the Davis sisters, Skeeter and Bonnie, but they really sounded bad. I thought, “I’m as good as they are.” The next week I got on the trolley with my little plywood guitar and went into the lobby of the radio station and introduced myself to Aubrey Mayhew, who was this sharp-looking guy with slicked back hair. I said, “I’d like to audition”, and he said, “Okay”, and took me into the big studio where I got my little guitar out and put it on backwards. I probably weighed about 120 pounds. I sang “Honky Tonk Blues” and “Music Making Mama From Memphis”, which was a Hank Snow song. So he said, “Do you want to be on the radio”? I said, “Yeah,” and that afternoon I was on the radio! Aubrey assigned me to a band from Torrington, Connecticut, called Cappy Paxton and the Trailsmen. This was 1954, and I was 16 years old. I’d seen Jack and Buzz Busby and Scotty Stoneman on the Jamboree show, but they had gone back to their various homes, so I never did meet Jack at that time. If I had gone in three months earlier, I would’ve met them. I saw them play, and they were a wild little trio. So that’s how I got started there. I did that for three or four months, then I went away for the summertime. When I came back, the whole show was gone. They changed the format of the radio station and everybody was gone. There was nothing going on. I had worked all summer long for a farmer, picking berries and selling vegetables by the side of the road. I had saved up enough money to buy a brand-new D-18 Martin guitar for $135. So I had this guitar, but I didn’t have anywhere to play or anybody to play with. On Christmas of 1954, my mother gave me a book, a collection of folk songs collected by Carl Sandburg, the American poet. I just started going through that book and I also found a record store in the back of a bookstore in Boston that carried folk records. I bought a Leadbelly record and a Pete Seeger record and some collections of Southern and Appalachian music. I was kind of just doing this stuff on my own, learning these folky songs. There was no country music on the radio anymore, so I was kind of disconnected from it. I went away to college eventually, and in my third year of college, 1959, I met this kid who was learning how to play the banjo. His name was Bill Keith. He had bought the Pete Seeger instruction book and had gotten to the last page where there was a section about Earl Scruggs and the Scruggs style of playing, which he was just learning. So I started playing with Bill Keith, who turned out to be one of the greatest banjo players that ever lived. He developed a new style of playing, and lots of people imitated his style. So we started playing in college, and when we would go home to Boston for family visits or holidays, we discovered all these coffeehouses had started up that had folk music. They would always have a hootenanny where anybody could get up and play. Bill and I started doing those hootenannies. That’s how we started performing together.

There was a guy in Boston, named Manny Greenhill, who was managing Joan Baez, who was singing in one of the coffeehouses. Manny liked us and gave us our first paying job, opening for another singer at Manny’s club called The Ballad Room. We opened a show for Joan Baez at Dartmouth College in January of 1961. It was an amazing show. Joan was just starting out and was still working on her first album. This place went crazy over Joan and they actually liked us too. We were playing some bluegrass songs and some folk songs. There was a coffeehouse in Cambridge, Massachusetts, called the Club 47, and we started playing there once a week. We met this great singer and mandolin player named Joe Val. Joe and his friend Herb Applin, who also sang and played fiddle, were a duo, and we invited them over to play with us at the Club. So all of a sudden we had a bluegrass band. We played Bill Monroe stuff and Flat and Scruggs. It was very exciting. This guy named Paul Rothchild came in one day and started hanging around. Paul worked in a record store in Boston, and he sensed that this was a scene. There were other people in this scene; an old-timey/bluegrass band called The Charles River Valley Boys, a wild blues singer named Eric Von Schmidt, a folk singer named Tom Rush, Geoff and Maria Muldaur, Jim Kweskin, lots of people. Paul Rothchild decided that he wanted to record us and the people at the Club 47. So Bill and I did some recordings with Paul and, in the meantime, the whole folk music thing really started happening, and Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, and Peter, Paul and Mary all became stars. It was a really exciting time. Bill Keith eventually got to play with Bill Monroe and his Bluegrass Boys. He came down to Nashville in ’63, and I came down in the summer of ’63 and spent about a month. That was my first time in Nashville, and we got to know a lot of the bluegrass players, like Jim and Jesse, The Osborne Brothers, and, of course, Bill Monroe. I got a Fulbright Fellowship to go to Greece for a year, in ’63/’64, which I couldn’t turn down. I had to go there, I had been reading about Greece for years. I took that year and did that and, when I got back, I came to the realization that I wasn’t good enough to be an artist. I didn’t think I had the drive to be an artist and devote myself to it totally. I did have an ability to organize things, so I took over running the Club 47. I didn’t know anything about it, but the manager, Byron Linardos, showed me how to make coffee and all the rest. I managed the Club for 2 1/2 years, and we had an incredible amount of music there. All the bluegrass bands played there, Bill Monroe, Lester and Earl, Jim and Jesse. We also had blues bands, like Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Paul Butterfield, and folk singers like Judy Collins, Gordon Lightfoot, and Arlo Guthrie. You name it, everybody played there. After 2 1/2 years of that, I got worn out. The artists were making so much money we couldn’t afford to pay them, so the club closed down in 1968. I got asked to get involved with the Newport Folk Festival held in Newport, Rhode Island every summer, by the man who ran it, George Wein. So I got involved in that and started coordinating all the talent for that and eventually went to work full time for them working on the jazz and folk festivals. I was also a tour manager and stage manager for a traveling jazz show. We played all the major arenas and ballparks. I got to meet all these great jazz musicians like Dionne Warwicke, Cannonball Adderly, Herbie Mann, Thelonious Monk, and Gary Burton. It was a privilege to work with them, and it was great fun while it lasted.

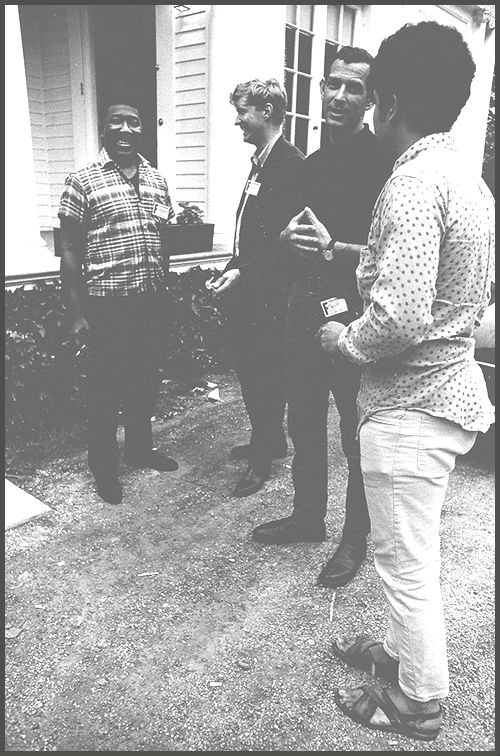

Rooney backstage at Newport Folk Festival – 1969

George Wein put a lot of rock and roll bands on the 1969 Jazz Festival. About 80,000 people showed up and it was really a mess. As a result, we couldn’t do the festivals in Newport anymore. So I didn’t have a job all of a sudden. I had met Albert Grossman who was the manager of acts like Bob Dylan, Peter, Paul and Mary, The Band, Janis Joplin, and I thought maybe he might need a tour manager. As it turns out, he didn’t need a tour manager, but he needed someone to run his new studio he was building in Woodstock, New York. So I took the job and moved to Woodstock in May of 1970. In my time off, I wrote a book called, Bossmen: Bill Monroe and Muddy Waters. The studio wasn’t actually finished yet, so my real job at first was construction foreman. My dad had been in the construction business and my uncle Jim was an architect, so I had grown up in that world and knew how to read blueprints and all that kind of stuff. So I was the right guy for the job, even though Albert didn’t know it. We got the studio on the air in about four months, and once it opened, it went 24 hours a day. It was called Bearsville Sound Studio. The Band and Taj Mahal recorded there. Bonnie Raitt made her first album there. Todd Rundgren, who was a young rock and roll artist at the time, took all my down time. He’d be in the studio all night long all by himself. You’d come in, in the morning, and there would be wires and tape everywhere. He recorded some big hits in there all by himself like, “Hello It’s Me.”

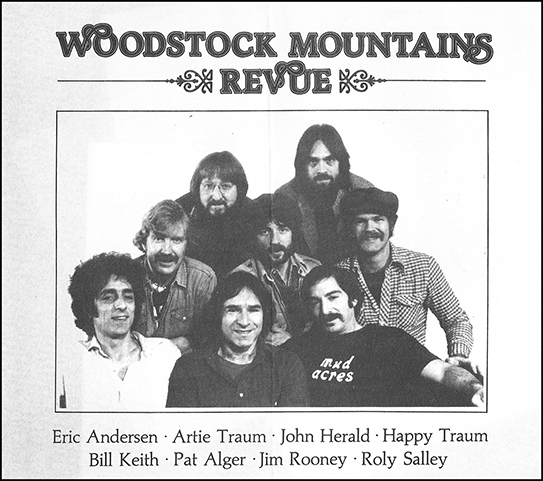

After I moved to Woodstock, Bill Keith and Geoff and Maria Muldaur moved over from Cambridge. We started jamming with Happy and Artie Traum and John Herald, which eventually led to the formation of a group called The Woodstock Mountains Revue. We played for several years around the Northeast, as well as in Japan and Europe. However, 90% of my time was taken up by my job. Albert was a great guy, but you could never do enough. I was on call any hour of the day or night and worked seven days a week, so, by the end of 1972, I told Albert I’d have to quit.

Rooney with Muddy Waters and friends – 1967

How did you meet Cowboy?

I had been working so hard, and my wife and I weren’t getting along, so eventually I decided to blow it all off. I stopped working, and my wife and I split up. I gave her the house and I bought a motor home and hit the road. Eventually, I rambled through Nashville and stayed there through the end of ’73 and well into ’74. I met a lot of people, like John Lomax, Townes Van Zandt, Guy and Susanna Clark and Richard Dobson. Guy and Suzanna took me over to Jack’s Tracks, where Cowboy was working with Townes Van Zandt. I didn’t know Cowboy, but I wanted to. They were working and I didn’t want to interrupt, so we just hung around for awhile and then left. So I never got to meet Cowboy on that trip, but I knew all about him. I got a copy of the first album Don Williams made on JMI Records, and I just loved it. It was such a different sound than what was coming out of Nashville at the time. It was a mixture of folk, acoustic, and country music, and I just thought it was great. In 1974, I went back to Massachusetts, knowing I would be back to Nashville at some point. I started a trio with the sons of Everett Lilly, and I wrote some songs. My friend, David Gessner, asked me to help a fine country singer from Maine, named John Lincoln Wright, make a record. I had done a little producing when I worked at Bearsville and I had done some mixing. So after we finished John Lincoln Wright’s album, David offered to pay for a session for me to put down some of my songs, which was very nice of him. He paid the pickers and paid for the studio time. I put down four or five songs. In April of ’76, I went back to Nashville with my tapes under my arm to see what I could do. I thought they were pretty good, and I was happy with the results. I went to see John Lomax over at Jack’s Tracks, and he listened to my stuff and said that he thought Cowboy would especially like a song of mine called, “Only The Best,” kind of a Cajun waltz. As luck would have it, Cowboy was in the next room, and Lomax brought him in to listen. Cowboy gave me a good five dollar show. He started waltzing around with a glass of water on his head and started singing along. He called people up and invited them to come over and listen to my song! I couldn’t believe it. This was a big day in my life. Cowboy invited me to a jam session the following day at Jack’s Tracks, so I came over, and there was Jim Colvard on guitar, Joe Allen on bass, Kenny Malone on drums, Charles Cochran on piano, and all these people whose names I’d seen on the back of the Don Williams album. They were all there and having a really good time. They were all very nice to me, and I just hung out with them. Marshall Chapman came by ,and we went out to get some beer and came back. Cowboy was so nice to me and so welcoming. I was living in my motor home, and it was parked right there at Jack’s Tracks. Cowboy was actually living at Jack’s Tracks at the time, and I knocked on the door Sunday morning and he let me in. Cowboy knew all about the scene in Boston. He knew Joe Val and knew who the Lilly Brothers were. I didn’t have to explain any of this stuff to him. He also liked the fact that I played backwards and that I had gone to Harvard and studied Greek, and that I was odd, I wasn’t normal. Cowboy asked me to send him the master tape of “Only The Best” so he could “fool with it”. Cowboy had been in a bit of a funk because he’d lost a ton of money making his movie Dear Dead Delilah, and had gone to Texas to see what was going on there. His quote was, “There’s not enough Ampex’s in Texas,” so he came back.

I didn’t know it at the time, but he was selling Jack’s Tracks to Allen Reynolds, and he was selling part of his publishing. He was broke. I knew nothing of this, and I thought, “Wow! This guy is really going to help me!” Allen Reynolds later told me that this was the first time Cowboy had shown any interest in recording for a while, and he thought it was a good sign. I sent Cowboy my master and he dressed it up with Buddy Spicher and Jimmy Buchanan on fiddles, and himself on mandolin and harmonies, and mixed it. All for no money. There was never a mention of money in this whole proceeding. I got to know Allen Reynolds, and also met Bob Webster during that time. Cowboy told me to go back up to Massachusetts and do some more recordings with those guys and send a tape to Bob Webster and he would listen to them. So I did, and I would call from time to time. Webster was always very nice to me. He never put me off or told me he was too busy. After three months, I decided just to go back to Nashville and see what would happen. I had about $300, and I had some gigs lined up that summer. I got an apartment at The Americana, which was just off Music Row, and I ended up living there for 12 years! I started hanging out with Cowboy at his house on Belmont Boulevard, where he had his offices, but there was not much going on at the time. I would go back and forth to my gigs up North. By the fall, I didn’t have much lined up, and I was beginning to wonder if I was going to be able to stick this out. I came by Jack’s house one day, and all these guys were set up in the living room. It was a band called Peace and Quiet, which consisted of Spady Brannon, Chris Leuzinger, Dwight Scott, and a drummer named T’ner Krawczyn. They were rehearsing. They had a PA set up and everything, so Cowboy asked me to join in, and I did. I played “No Expectations,” which I had worked up with Bill Keith as a bluegrass song. They liked it, and I played a few more songs, and after we were finished Cowboy called me into his office and said, “You’re going to be my rhythm guitar player. You need to be here in tune and ready to play at ten in the morning. We’ll work until four in the afternoon. I’ll provide lunch and I’ll pay you $250 a week.” Talk about prayers being answered!

Cowboy had recently been signed to Elektra Records as an artist, and he was given a budget to make a record, so he was out of his hole financially, for the moment. The first thing he did was buy a recording console and put it in his office. Eventually, he turned the upstairs attic into a studio. We rehearsed every day, and later added some horns and started playing around town as Cowboy’s Ragtime Band. We played three nights a week at George Jones’ Possum Holler, which was a great gig. We had worked up at least 100 songs and played stuff like “Brazil” and “Undecided Now,” you know, dance songs. Then we had Big Rick Schulman and Little Richie Jarvis who could do “Soul Man” or “Desperado.” We did all of Cowboy’s songs. I sang a few. People like Merle Kilgore, Mel Tillis, or Webb Pierce would sit in. It was amazing! That went on through the end of 1976, and, in January, we went over to Woodland Studio and cut about four songs in about 20 minutes, one after the other. We knew the stuff and could do it at the drop of a baton. That’s how we started recording Cowboy’s album for Elektra. The $250 a week had stopped by Christmas, but I was picking up work here and there. Bob Webster was recording some stuff during that time, and hired me to play rhythm guitar. I was becoming very comfortable in the recording studio. In 1978, I went away for about six months and wrote a book about the folk scene in Cambridge called, Baby Let Me Follow You Down, with Eric von Schmidt. When I came back to Nashville, John Prine was recording with Cowboy, piling up tapes. Cowboy got me started running the board in the studio. I was skeptical at first. I told Cowboy that I wasn’t technically-minded. He looked at me and said, “You don’t have to be a mechanic to be a good driver, do you? You’ve got good ears. You know what music is supposed to sound like. You can do it. Do it.” Cowboy and his engineers, Curt Allen and Jack “Stackatrack” Grochmal, gave me some tips. Keep the needle in the middle, don’t mess with the signal if you don’t have to, move or change the microphone if it doesn’t sound right, and don’t use compressors or limiters. This really opened my eyes, because all these gadgets had come into recording, like limiters, compressors and gates. I had seen all these people up at Bearsville EQ-ing everything, and limiting everything on the way in and on the way out, and I thought there was something about this process that I just didn’t understand. Cowboy showed me that you don’t have to do all that stuff, and he didn’t want me to record that way.

I learned the proper way to mic a guitar or a fiddle, and different things. One day Cowboy called me over to the studio and Vic Damone was there, along with Joe Allen, Kenny Malone, and Charles Cochran, who by this time I was friends with. Cowboy asked me to record them, so I got everybody set up in the studio like I thought they should be. Vic Damone didn’t know that I had never recorded anybody in my life! I was really nervous. I was sweating bullets. Everything was sounding good and everyone was comfortable, so I pressed the red button and off we went. Then, of course, they wanted to hear it back, and I really didn’t think it would play back. I just had no confidence whatsoever. I played it back and it sounded fine, it was all there, and they all said, “Let’s do another one,” and that was the beginning of my engineering career!

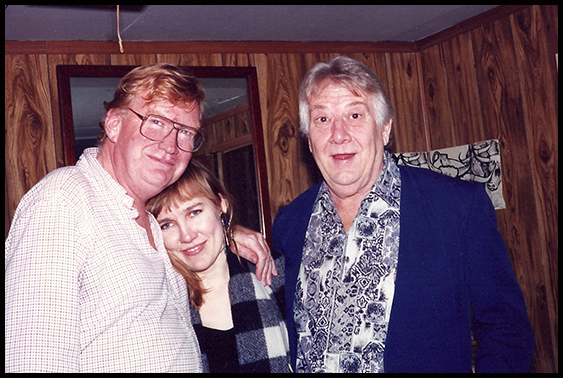

Rooney with Iris Dement and Cowboy Jack Clement

For the next five years or so, I recorded whoever showed up. I was kind of thrown into the deep end of the pool, but I managed to swim. I recorded Carl Perkins, Billy Lee Riley, Jimmy Rodgers, Johnny Western, Merv Shiner, Frank Ifield. You name it. I also recorded a lot of demos for the House of Cash, where I would cut eight songs and do all the overdubs the first day, then mix it all the following day. I did that for several months, and it was really good journeyman work for me. I learned how to work fast and get everything done. And it sounded good. As time went by, I wanted to bring some business in to repay Cowboy for his kindness. So I let it be known that I was engineering. Ken Irwin at Rounder Records started using me. I recorded some records for Rounder, including Alison Krauss’ first album. Cowboy would let me use the studio anytime it was not booked. That’s the kind of stuff you pray for. I recorded an album for Richard Dobson and we cut the whole thing in a weekend. Richard later invited me to a barbecue at his house and I met Nanci Griffith. Nancy had heard Richard’s album and really liked it. I had used Philip Donnelly on it. Philip had recently moved to town and I loved his playing. Philip started coming over to Cowboy’s and hanging out. One day we decided to record some stuff, and I did “No Expectations” and “Down South In New Orleans,” which Cowboy decided to release as a single on JMI Records, almost the last record of JMI. I was just thrilled. In 1984, we cut Nanci Griffith’s album “Once In A Very Blue Moon.” I hired Jack “Stackatrack” Grochmal to engineer, because I didn’t think I could engineer and produce at the same time. We cut 13 songs in two days, overdubbed for two days, and mixed for two days. Nanci went home with that album under her arm. That turned out to be a really good album, and I had put it all together. That was the first time I had done something on that scale, and it gave me confidence. I really started thinking, “I can do this.” That’s when I really got serious about producing and realized it was something I could do. I always felt, with Cowboy, that what he did for people was give them opportunities, and the only thing that ever disappointed him was when people didn’t take advantage of the opportunity or took advantage of him. I always felt a real sense of gratitude and obligation to pay it back as well as I could.

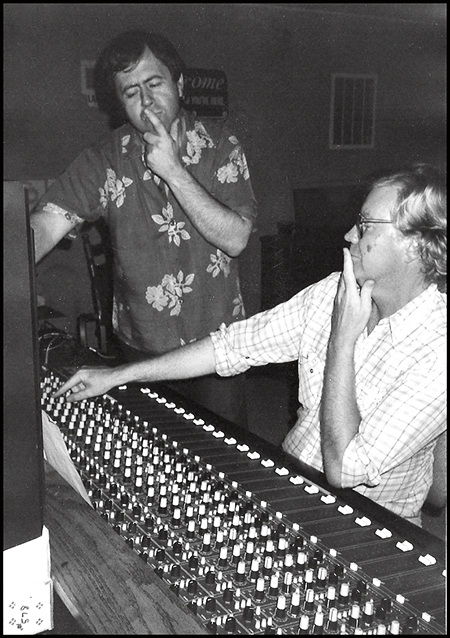

Jack “Stackatrack” Grochmal and Rooney making important musical decisions.

I have always found Nashville to be a very generous town. All the players and the songwriters are so talented and so available. On the first demo session I ever did for Pat Alger, I had asked Kenny Malone, Joe Allen, and Charles Cochran to play on it, and they wouldn’t take any money for it. Pat got a cut out of that session. That kind of generosity is what Nashville is all about. I couldn’t think of a better place for me to be. I was just so lucky that I crossed paths with Cowboy when I did, and all the people that I met through him. Nashville turned out to be a very lucky place for me to be. I hung out with Bob Webster a lot, observing the publishing side of things. The heyday of Jack’s publishing company was over when I came along, but one of my tasks was to make a copy of the entire Jack Music catalog to DAT. So I got an opportunity to listen to the whole catalog, and just doing that alone gave me such an understanding of what was going on as far as demoing songs was concerned. I watched Webster administer the catalog, and then Terrell Tye came along. Webster offered to teach her what he knew, and together they computerized the process when not everybody was doing that. One night I was at Cowboy’s with Curt Allen, and we were having a few drinks after work. When Curt had a few drinks he would have a little edge to him, and he looked at me and said, “Rooney, what are you going to do?” I was in my late 40’s at the time, and I was eking out a living. I was a $12 an hour engineer and could produce a record for $750.00. I was keeping the wolves away from the door, but I had no money, no savings. I was enjoying myself and it wasn’t really about money. However, that question that Curt asked kind of niggled at me. “Here I am almost 50 and I have no plan.” So I got the idea to start a publishing company. That seemed to be a good way to make some money. I realized that I had these people like Pat Alger, Lyle Lovett, and Nanci Griffith coming through my hands and I had nothing to offer them in terms of song publishing. I invited Terrell Tye to lunch and asked her about possibly starting a publishing company. Terrell was working one day a week for Allen Reynolds, so we decided to talk to Allen. Allen told us that he had wanted to have a publishing company all of his life, and it was quite interesting how it all gelled like that. His only stipulation was that he wanted to involve Mark Miller, who had become his main recording engineer at this point. Allen is such an honest and thoughtful person. I trusted anything he wanted to do, and I couldn’t have gone into business with a better person. I really wanted to build the publishing company around Pat Alger, so I went to him and asked, “What will it take to keep you writing all the time?” He said, “I want to keep half of the publishing and I need about a thousand dollars a month.” I said, “I think we can do that.” And that’s basically how we started. Pat included the song “Going Gone” in the package that Allen had just cut with Kathy Mattea and that turned out to be our first number one single as Forerunner Music. Kathy was selling 200,000 to 300,000 records, and that was considered good at the time. But Pat had co-writers, and by the time we got down to it, we were looking at 12%. We weren’t going to get rich on that. Then Garth Brooks entered our life and everything changed. Pat Alger and Garth turned out to be a very good writing duo. I met Hal Ketchum during that time, and we signed him as a writer. As soon as I heard him in the studio, I knew he had a voice for radio. We got Hal a deal with Curb Records, and that turned out to be great too. Allen and I produced the records on Hal, and that was my first and only experience in producing “hit” records. I was producing records in the folk area with people like Nanci Griffith, John Prine, and Iris Dement, but we were not really thinking about radio airplay. Working with Allen was a great eye-opener for me.

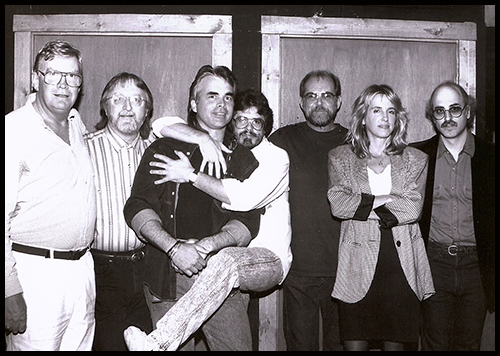

The four Forerunners w/ Pat Alger, Hank DeVito, and Hal Ketchum making BILLBOARD’S 1993 Country Single of the Year

Rooney, Pat Alger, Hal Ketchum, Mark Miller, Allen Reynolds, Terrell Tye, Hank Devito

We had a lot of success with Forerunner for several years with wonderful writers like Pat Alger, Tim O’Brien, Pete Wasner, Tony Arata, and Shawn Camp, but the business side of things in Nashville was getting to be no fun anymore. There were too many middle-men and marketing people involved who had the final say on a lot of things. Then there was the whole digital download thing just starting, where people were able to access music for free. After 14 years, we decided to sell the company, and, in retrospect, it was the right thing to do. After that I lived and worked in Ireland for a while. I loved living there, but it’s gotten so expensive and I’m getting to a point in my life that I can’t spend money I don’t have. I’m living off the money I made from the publishing company and I have to make it last. I seem to be in very good health and could go on for a long time. I can’t blow it. I’m not officially retired. I just finished an album in Salt Lake City, and I’m doing some small stuff. I did a record with Tom Rush two years ago that was the Folk Album of the Year. I enjoy making records more than anything. I play with Rooney’s Irregulars at The Station Inn here in Nashville a few times a year. It’s fun and it keeps me in touch with the guys I’ve worked with the past 30 years. Although I now live in Vermont with my wife Carol Langstaff, I still keep my apartment in Nashville and spend about 2 1/2 months a year here. I stay in touch, and if I had more work I’d be here more. What are your proudest career moments? I’m very proud of what we did at Forerunner, and I’m really proud of the records I’ve made with Nanci Griffith, John Prine, Iris Dement, Townes van Zandt, Dave Olney, Hal Ketchum and Pat McLaughlin, to name a few. I just love these records and never get tired of listening to them. To me, it has been a great privilege as well as a pleasure to be able to work with people of that quality and have it be fun and successful. All those records that I’ve made have been successful records for them and helped their careers. We got in at a time when you could actually sell some records. John Prine or Nanci Griffith could sell four or five hundred thousand records. Those days are over. Everybody’s downloading everything and you’re just not going to get paid on an awful lot of it. Nowadays, all the artists make their money by playing live.

Sam Bush, Rooney and Bill Monroe

What do you like to do for fun? I like to play music and tend my garden up in Vermont with my wife Carol. Anything you would like to promote? I don’t currently have a website, but I’ve been thinking about doing one. I am writing some sort of a memoir, and if I ever get it together that might be a reason for me to do a website

Jim presenting Lifetime Achievement award to Pete Seeger – Folk Alliance Conference 1995